In the movie Pulp Fiction, Quentin Tarantino serves John Travolta and Samuel Jackson what he calls “gourmet coffee.” It was the early days of the specialty coffee revolution and what Quentin served was coffee that was flavored to taste like something else. It was a particularly ugly process of using propylene glycol as a carrier agent to impart an artificial flavor to stale coffee beans – and it was wildly popular. Fortunately this flavored model died off as consumers discovered Specialty Coffee. But flavored coffee has made a comeback recently in a new form in the Specialty world: Fermented Coffee.

The coffee tree, or genus Coffea, belongs to the family Rubiaceae, of which there are some 500 genera and over 6000 species. Some are trees, most are shrubs, a few are herbs, but they are all tropical, and found in the lower story of forests. The coffee tree is more of a shrub than a tree, but left untended can grow to some 20 feet. It is evergreen and never drops its leaves. Like many other evergreen plants in the tropics, it has evolved its own bug repellent: caffeine. Caffeine is a stimulant and over-excites most insect species that come in contact with it. There are a number of varieties to the Coffea genus: various authorities give a range of 25 to 100, but only three have any commercial concern: Coffea Arabica (comprising 80% of the market), Coffea Canephora (better known as Robusta, with about 20%), and Coffee Liberica (less than 1%).

The Arabica variety is an allotetraploid inbreeder, which means the flower contains both sexes and can therefore self-pollinate, unlike the Robusta tree, which has to be bred with two trees. It is by virtue of good fortune – or happy coincidence – that the tree that first made its way to India and then to Amsterdam was of the Arabica variety and not Robusta. The subsequent spread of coffee around the world would have been nearly impossible otherwise. Over the years, mutants, or variations, to the Arabica tree have emerged. Today there are some 50 plus variations, called cultivars. The first identified was the bourbon cultivar, distinguishing the tree from those cultivated on the island of Reunion. The trees coming from Yemen seeds are recognized as the original type, or typica. These two, Arabica Bourbon and Arabica Typica, are nearly identical and impossible to ascertain from herbarium specimens. Both are considered heirloom varieties that are most prized for flavor quality.

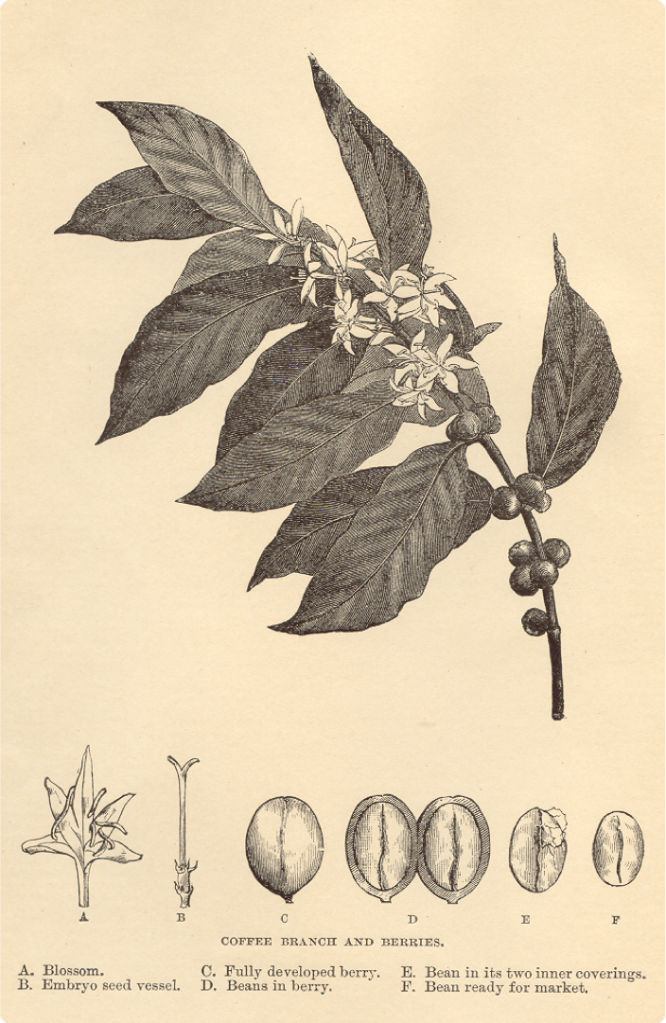

After the rainy season the coffee tree bursts into small white blossoms that smell like Jasmine. As these blossoms are pollinated the petals fall away and a cherry forms. Within each cherry there are usually two seeds, lying side by side, that cause the flat part of the coffee bean. Occasionally, only one seed forms, creating a smaller, rounded seed called a peaberry. Every now and then, three seeds form, one growing into another creating a shell like bean called a mother bean. Regardless of the number of seeds inside, they are all encased in a slimy substance called mucilage. This layer is, in turn, surrounded by the fruit of the cherry and, of course, the skin.

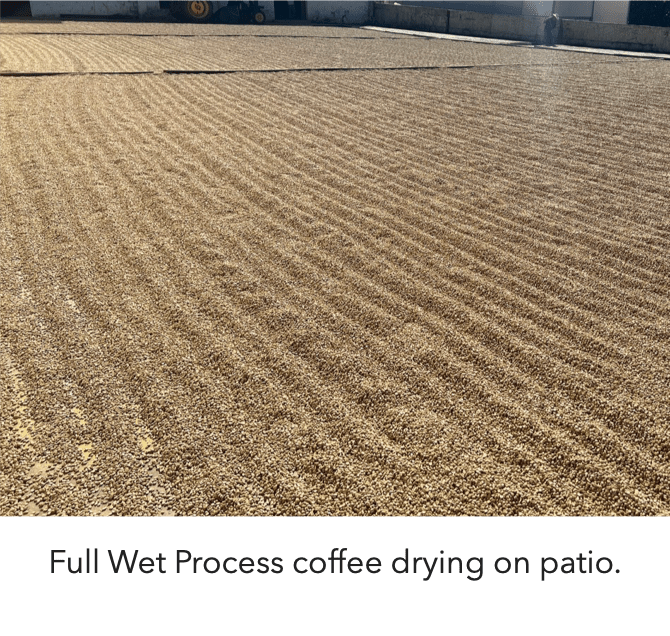

The processing of the coffee cherry involves getting rid of all these layers around the seed itself. It is here that we make our first step defining specialty coffee from conventional coffee. For much of conventional coffee history, quality was defined by the cleanliness of the preparation from cherry to bean. It was generally accepted that good coffee was clean coffee, free from off flavors that could result from processing. Professional coffee tasters were skilled at detecting tainted characteristics due to processing and rewarded growers for clean, well processed coffee beans. The method generally preferred was the “full wet” method of washing the fruit from the beans and evenly drying them on patio beds until they were of uniform moisture. If the process is done correctly the coffee beans will display a clean bright citrus acidity of fresh lemon. This is known as “good acidity” in the conventional coffee trade.

However, the implementation of full wet processing throughout the global coffee growing community faces two significant hurdles: the first is the abundance of fresh water; the second is the investment in the necessary infrastructure in the form of wet processing mills. Certain countries invested heavily in such infrastructure, such as Colombia and Costa Rica, and were rewarded in a premium for their clean coffees, whereas countries such as Brazil competed for lower prices rather than quality. This method also tended to favor estate grown coffees as the landowners were more likely to receive the necessary financing to invest in infrastructure improvements. The development of small farmer cooperatives in recent years has mitigated this to some degree.

By having a uniform method of processing, the coffee trader focuses on any defects or taints that may negatively impact the coffee’s flavor. This defect/taint-free coffee is delivered to the roaster, who must then tease out a roast profile based on its terroir – a particular challenge especially when considering the similarity of growing practices among estate-grown coffee, many of which use similar fertilizer, agro-inputs, and little to no shade cover. This leads to few environmental variations in terroir beyond elevation and rainfall. The result is a coffee that is clean, defect free and uniform but lacking any real distinction. The premise here is the absence of bad equals good – or at least not rejected by the roaster. Terroir does have a positive effect on coffee – but only when the actual environment the coffee is growing in reflects real biodiversity in flora, fauna and growing techniques – a fact that small farmer cooperatives have capitalized on.

A new generation of coffee aficionados, however, is throwing the old rules out. Bringing the same sensibilities that brought back the bacteria to make sour beer, today’s specialty roaster is rewriting what makes coffee good. Processing methods that in the past were considered rudimentary and tainting the coffee’s flavor are now intentionally being utilized to alter the coffee’s flavor in the hopes of creating distinction – something that stands out on the cupping table. Something special.

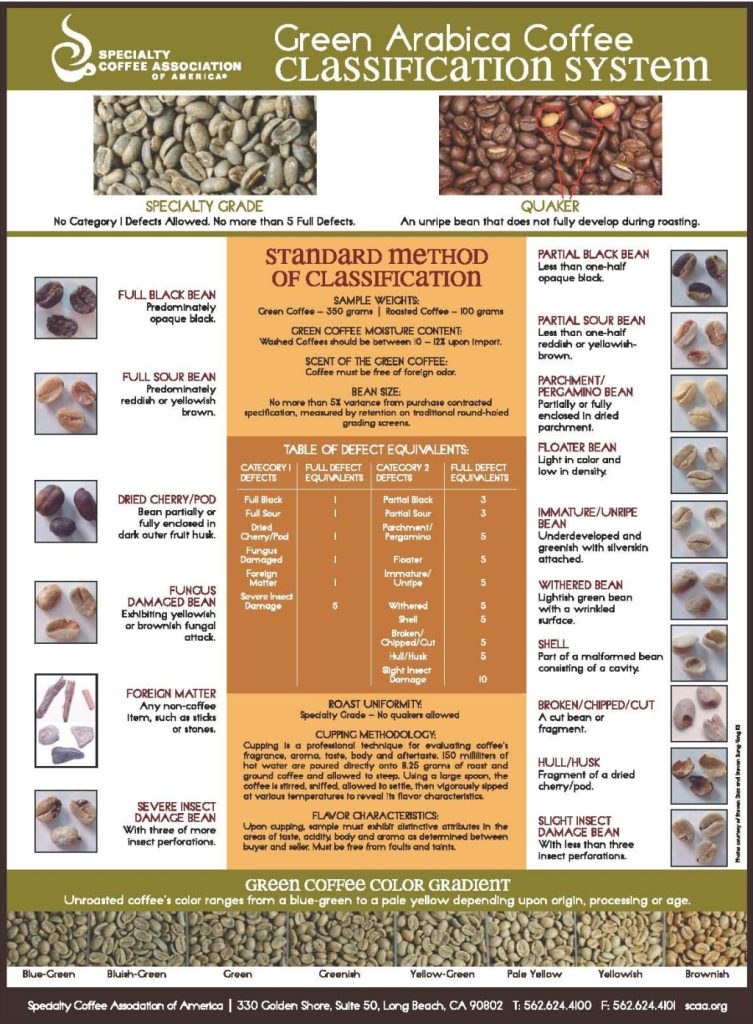

First, a discussion about defects and taints is in order. Defects are things that are recognized in the industry as anything that negatively impacts coffee quality. Things like over-ripened or under-ripened cherries, black beans, sour beans, sticks, stones, insect-infestation, disease, etc are all universally understood as defects. Defects are easily identifiable by simply looking at the green coffee sample. The Specialty Coffee Association has developed a classification system based on the allowable number of defects a sample may have in order to be considered Specialty Grade. It is generally accepted that defects will taint the coffee’s flavor. Taints are variables that impact the flavor quality. Things like mold, ferment, petroleum, past crop, etc., will negatively alter a coffee’s flavor. Taints are identified by sampling the coffee in a prescribed manner known as Cupping.

The way a coffee is processed also impacts the coffee’s flavor. While wet processed coffee results in clean, uniform flavor, other processing techniques leave recognizable characteristics. These characteristics may taint the flavor but may not necessarily be considered defective. In short, all defects are taints but not all taints are defects.

Historically, coffee traders were trained in “defect cupping” to identify taints and reject coffee shipments that reflected poorly on flavor quality. The coffee would be roasted very light, a “trade roast,” to emphasize acidity to determine crop quality. In this model acidity was a pass/fail criteria: coffee that displayed something other than citrus may be cause for concern. But now taints are not universally understood to be negative, especially when it comes to processing fermentation. The general rule of thumb is if one or two cups in a sample display a taint that is a defect, if they all uniformly display a taint then it is intentional.

In recent years many of the characteristics of fermentation that would have once been considered defective are now thought of as favorable. It is more a question of scale than kind. Cuppers still recognize ferment as a defect, but it is only a defect if it is perceived as being overdone – “over” fermented. This is due to the adoption of “Trade Roasts,” now commonly called Light Roast, as an indicator of quality coffee itself among the current generation of coffee roasters. In this roast style, acidity dominates. For this generation, acidity is flavor. The only variation in flavor then would be a variation in acidity – described by a litany of fruit names. The best way to affect such acidity is in post-harvest fermentation.

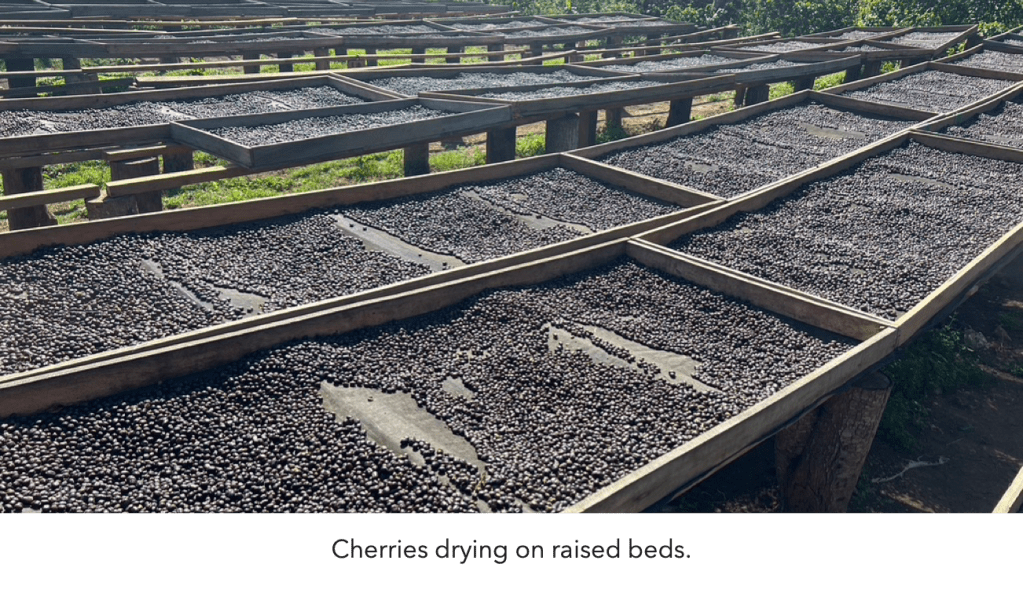

Post-harvest fermentation involves the revival of a number of processing methods that leave a taint on the coffee’s acidity. The first to gain acceptance was “natural” or “dry” processed coffee. This method dispenses with the immediate pulping of the cherry by leaving the fruit on the bean to dry in the sun and has widely been used in areas where there is a lack of water for processing. In the past, these coffees would have been considered lower value due to the rudimentary processing method (and often uneven results). It is not uncommon today to find producers setting aside a portion of their crop to offer natural processed micro-lots alongside their traditional fully wet processed coffee. Instead of offering it at a discount, it is now a premium.

Similarly, what used to be considered wet processing’s cheaper cousin, semi-wet, has enjoyed new notoriety as “pulped natural” or “honey processed.” These processes originated in areas where water was plentiful but infrastructure for wet mills was unavailable. Many small producers have long processed their small lots of coffee in this manner, using a small pulping device and laying out the pulped beans out to dry. Depending on how clean the beans are when drying determines whether the technique is “white honey” or “black honey.” The amount of debris left on the bean will cause varying degrees of alteration, for better or worse depending on your preferences. Small producers in the past were encouraged to clean as much fruit from the bean as possible to mimic the quality of full wet processed coffee. Now, certain producers intentionally leave varying amounts of mucilage on the bean to affect the fermentation.

Beyond simply reviving old or primitive methods, there has been an explosion in “experimental” coffees by many estate producers and exporters. If an estate owner didn’t want their wet mill to go to waste they could experiment with extended fermentation times or double fermentation. With double fermentation, the coffee cherries are allowed to soak overnight – and spend some additional time in the fermentation tank – before going to the de-pulpers. Some prefer this method, since it is a much cleaner way to control fermentation. Others may experiment with enhanced fermentation, by adding additives to the fermentation tank – like citric acid – to boost the acidity or create other flavor characteristics.

Finally, some growers have experimented with maceration of the cherries before pulping. The idea here is to control the amount of oxygen to the fermenting fruit. This can be done as simply as placing a tarp over a pile of fruit, to sealing the cherries in bags, or even sealing them in containers such like drums. This process is usually described as carbonic maceration or anaerobic maceration and typically results in a more pronounced winey – or, if overdone, boozy – character.

The flavor characteristics that result from post-harvest fermentation have recognizable taints that modern roasters celebrate with descriptors such as stone-fruit, raisin, strawberry, quince, etc. Whether these characteristics represent a move towards higher quality lies in eye of the beholder, or in our case, the mouth of the taster.

These methods have been successfully employed as a value-added measure for many producers since the new model of cupping Specialty coffee, the “Q-Grade“, weighs acidity above all other characteristics. For many, the grail is to create a coffee that cuppers describe as “juicy.” With perpetual low prices that have come to define the coffee trade it is no wonder that producers would experiment with ways of adding acidity to boost value. The disconnect is attaching these flavors to terroir, botanic species or, indeed, quality. Many modern roasters wax poetic about altitude, varietal, and farmer dedication when the flavor attributes are principally derived from post-harvest manipulation. The specialty coffee industry, rather than promoting bio-diversity (which would have the additional benefit of combating climate change), has taken the easy way out. It is the modern equivalent of flavored coffee – a way of taking conventional coffee and imposing a flavor on it rather than highlighting an inherent quality present in the bean. Or, more plainly, to take something conventional and call it “specialty.”